My laptop was a ticking time bomb.

Deep within a nested hierarchy of folders in the machine’s My Documents folder, in an archive eight levels down, sat 722 Social Security numbers. For nearly 10 years I had walked around with those Social Security numbers tucked away in my laptop as I carried it to trade shows, conferences and my office.

I was a walking data breach waiting to happen — and I didn’t know it until I was asked to review Identity Finder. Now I feel like the poster boy for why businesses need to think about using this type of product.

Identity Finder, from the company of the same name, is a discovery tool for home or business users that searches through data stored on individual Windows and Macintosh computers for personal data such as credit card, Social Security, bank account, driver’s license and passport numbers; personal addresses, phone numbers, passwords — even your mother’s maiden name.

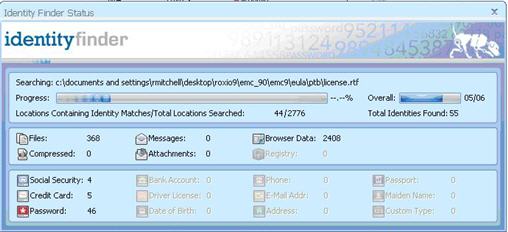

Identity Finder keeps a running tally of discovered identity data.

Choose your flavor

Identity Finder comes in Home, Professional and Enterprise versions for Windows, as well as a more limited Mac edition and a very limited free Windows version. Capabilities vary greatly between editions, so it’s important to carefully compare features to make sure you buy what you need.

- On the low end, the Free Edition is limited to password and credit card number searches within browsers and the My Documents folder.

- Next in line is the Home Edition, which searches the full range of identity data types but doesn’t allow custom searches, is limited to a set of common file types and won’t search Outlook PST files. It also has no quarantine function. It costs $19.95 for a single-user license or $39.96 for a three-user license.

- The Professional Edition supports a broader range of file types, does a better job with e-mail, and supports the quarantine function. It can also scan for patient health data and payment card industry data. It costs $29.95 for a single-user license or $59.85 for a three-user license.

- On the high end, the Enterprise Edition can search Exchange Server e-mail files. It enables remote control of searches and receives results back from every desktop. It will search internal and external hard drives and personal storage areas on the network. It also can search server-based databases compatible with the Microsoft OLE DB API, and Web sites. There is an annual fee of $20 per seat plus $1,000 per server ($5,000 minimum), or you can opt for a one-time fee of $40 per person plus an annual maintenance fee of 20%-25%.

While Identify Finder’s default search looks for Social Security, credit card and password data, the program’s real power comes from its ability to perform “AnyFind” searches for generic identity data types. AnyFind expands the search to include bank account numbers, driver’s license numbers, dates of birth, e-mail addresses, phone numbers and personal addresses.

You can also include additional search criteria, such as passport numbers, mother’s maiden name and “worldwide,” an option that searches for Social Security number equivalents used in other English-speaking countries. Finally, you can create custom identity types.

The Professional, Enterprise and Mac editions of Identity Finder allow you to search for specific data in a single search, or you can create a profile that includes specific criteria you want to search for every time you run Identity Finder and schedule regular scans after hours.

I tested Identity Finder Professional Edition on an IBM ThinkPad X60 and an older eMachines desktop PC, both running Windows XP, and an Acer Aspire 5516 laptop running Windows Vista. I also tested the Macintosh edition on a MacBook Pro running OS X 10.5.8.

Searching for identities

I started by running an Identity Finder scan on my recently retired Computerworld-issued ThinkPad using the default search settings. The process tied up my machine for several hours as Identity Finder sifted through more than 9GB of data, including all of my work files going back to May 2000. I then ran the Mac edition on my MacBook business laptop, which included the same set of data, before turning to a few of my own home (Windows) computers.

Identity Finder Pro initially presents a simple “wizard” interface that hides the advanced features of the product. It lets you run the default search for any instances of Social Security numbers, credit card numbers and passwords. You can also add categories, search for specific data within those categories, or go to the Advanced Interface to create more sophisticated searches.

Identity Finder has its own filters for a few specific file types, such as PDF and Microsoft Office 2007. For others, it uses the IFilter technology built into Windows, which is used by the Windows Desktop Search function.

It can read popular compressed file formats such as .zip and .tar, and it searches all data stored by Internet Explorer or Firefox (where it uncovered about 50 unencrypted passwords on my system). However, according to CEO Todd Feinman, Identity Finder has no plans to support other browsers, such as Chrome or Safari. It also can’t read encrypted files, nor does it have the optical character recognition capability necessary to read sensitive data captured in images of invoices or other scanned documents.

However, the biggest limitation is around e-mail. The Professional edition supports searches of data stored locally by the Outlook, Outlook Express, Windows Mail and Thunderbird e-mail clients, well as any client that uses the mbox mail format, such as Eudora. However, if you use Exchange Server, you’ll need the Enterprise edition to search either your locally cached or server-based copies of your mail and public folders. Identity Finder does not support other enterprise e-mail systems such as Lotus Notes.

Identity Finder also can’t crawl data in the cloud, so if your company uses cloud-based e-mail like Gmail, or if you use your browser to access personal Web mail, as I do, you’re out of luck. Because I use Gmail and Exchange, my search yielded no results associated with my e-mail accounts.

When I was done with my first pass (using the default AnyFind for Social Security numbers, credit card numbers and passwords), I had a report that included 858 files, most of which were Social Security numbers.

On the second pass, I had Identity Finder search on all nine identity data types that are found by the AnyFind feature and came back with an additional 234,709 results — a totally unmanageable number. Lesson learned: Using the AnyFind feature on identity data types such as e-mails, addresses and phone numbers casts the net too widely. Practically speaking, the AnyFind function is useful only for more sensitive, structured account numbers such as those for bank accounts, credit cards and passports.

Using more specific search criteria in the other categories can help pare down the results. Even then, you can end up with very large result sets. Fortunately, you can apply filters to organize the data by location, identity data type or any other search criteria you choose.

What does Identity Finder find?

When I let Identity Finder Pro crawl my work computer, it found the following:

- 722 Social Security numbers, including federal tax IDs on contract documents, two instances of my Social Security number and my wife’s number on a completed medical insurance PDF claim form that was never deleted, and a reference to my Social Security number in a personal letter asking a financial services company not to use it in identifying me.

- 119 passwords, including 50 stored in unencrypted form by Firefox, multiple usernames and passwords associated with various FTP download sites, several log-in names and passwords for conference calls, and a spreadsheet that contained more than 50 usernames and passwords for various online Web sites and accounts.

- 39 bank account numbers, 15 of which pointed to actual personal and professional accounts. These included my American Express credit card number from a downloaded and forgotten PDF statement, and a family member’s Visa credit card number embedded in correspondence.

Identity Finder came up with very few false positives when it searched for passwords and Social Security numbers. I caught quite a few false positives with bank accounts, but to be fair, most were fake bank account numbers embedded in PowerPoint and PDF presentations. Likewise, all 31 birth dates discovered were fakes in sample data associated with a Microsoft Access demo and a PowerPoint presentation.

I got interesting results on the other two Windows-based systems. On the Acer, Identity Finder found Firefox passwords and not much else. However, on the eMachines desktop, which is my primary home machine, Identity Finder discovered eight instances of credit card numbers (much to my consternation), 23 instances of Social Security numbers, all belonging to me or my spouse, 105 unencrypted passwords stored by Firefox, and eight bank account numbers, all of which were false positives.

Identity Finder — Mac Edition

The Mac Edition has the same basic look and feel as the Windows editions but lacks many of its older, more established sibling’s features. Feinman says the company has spent more time developing its Windows version because of its focus on business users. “The Mac version trails the Windows version by about a year,” he says.

So, what’s different? While the Mac Edition supports searches for the same identity data types, the AnyFind option is available for fewer of them. There’s no summary window to tally the total number of items discovered in each category, and results can’t be filtered. More important, searches don’t include any e-mail or browser data, you can’t redact sensitive data from discovered files, and it can only search the local disk — no external or networked disk drives.

The current Mac 2.1 client also isn’t a full partner in the Enterprise edition: It can report search results to the central console, but you can’t remotely schedule or start searches like you can with Windows clients.

That will change with Mac Edition 3.0, which the company says will ship later this month. The new edition adds the missing summary status window and allows the Enterprise edition console to set policies and schedule tasks on Mac clients. Identity Finder hopes to have a new version that supports searches of Apple Mail and the upcoming Outlook client for the Mac later this year.

I tested both Version 2.1 and a beta version of 3.0 on a MacBook Pro. On its first run, Version 2.1 crashed about one minute into the search. I relaunched the program and ran several more searches without any problems. The beta of Version 3.0 installed and ran without any significant issues.

When applied against the same data set I used to test the Windows version, Identity Finder Mac Edition returned the same results, with one rather large exception: It missed some 50 unencrypted passwords stored by the Firefox browser. (You can close this security hole yourself by going to the Security tab in the Preferences dialog and unchecking the option enabling Firefox to remember passwords, or by by checking the “Use a master password” box, thus encrypting your passwords.)

The Mac edition has the same basic look and feel as the Windows editions.

I found the lack of results-filtering tools to be a drawback when dealing with the large set of results generated after my first search. For subsequent searches, however, that shouldn’t be as big of an issue, since presumably far fewer results would be found.

Mac Edition works with OS X 10.4 or later; it costs$19.95 for a single-user license or $49.96 for a three-user license.

Cleaning up the mess

Once you’ve collected and reviewed your data, Identity Finder Pro lets you select each found file that contains an identity item, preview the identity data in context, and take any of several different actions to deal with it:

- “Scrub” sensitive data from within the source document. This works only if it is an Office 2007, text, HTML or comma-separated variable file.

- Shred the file, through a multiple-pass deletion process that renders it unrecoverable. This can be dangerous, however — for example, Identity Finder found multiple instances of “Social Security numbers” embedded in a file associated with LastPass, a password manager Firefox add-on. Those were not Social Security numbers, says Sameer Kochhar, director at LastPass, but JavaScript coding. Had I shredded or quarantined that file, LastPass would have broken and I would have had to either restore the file or reinstall LastPass to get it working.

Firefox encryption

One of the biggest groupings of sensitive data that Identity Finder came across in my tests was the 50 or so online username and password combinations I’d allowed Firefox to store for me on my business laptops. What Firefox doesn’t tell you is that you need to turn on encryption under Tools –> Options –> Security settings and create a master password if you want those stored passwords encrypted.

“If a master password is not used, the passwords are stored in plaintext and could be discoverable by any malicious software run on the machine,” says a spokesman for the Mozilla Foundation. Like many users, I blithely gave Firefox permission to remember passwords and never gave it a second thought. I was completely unaware of how those passwords were being handled.

Identity Finder can disable the storage of usernames and passwords in Internet Explorer and Firefox, and create a master password for Firefox — but Mozilla does it better. As you type in a new master password, the Firefox dialog box includes a “Password quality meter” that measures how strong your password is.

- Encrypt the file. When you encrypt files (using your application’s built-in encryption, Identity Finder’s 256-bit AES encryption or a third-party encryption tool such as PGP) or save search results, Identity Finder prompts you to create a profile password. Unfortunately, it does not enforce the creation of a strong password, nor does it provide guidance (such as a displaying a “strength meter”) on how to create one. This seems a bit strange for a product that stores reports containing summaries of highly sensitive data. (An optional setting to enforce strong passwords is available in the Professional and Enterprise editions but is turned off by default.)

- Quarantine it. The quarantine feature allows the user to move offending files to a new area and encrypt them. A nice option here: You can configure Identity Finder to leave behind a text file with the original file name. When opened, it includes this message: “The original file … contained unsecured, personally identifiable information. It has been quarantined to [location].”

- Send it to the Windows Recycle bin. As an Identity Finder pop-up warns when you mouse over this option, documents sent to the Recycle Bin are easily recoverable, so why offer this option at all? According to David Goldman, president and chief operating officer, Identity Finder added the option after some enterprise customers complained that their users could accidentally shred important files. (By using the Recycle Bin, the user can set aside files containing identity data, moving them there for later review before shredding.

- Ignore it, in which case it won’t come up again in subsequent searches.

The bottom line

Identity Finder Professional does a good job of scanning Windows computers in a business setting, so long as you understand what it does and does not search. You’ll need the Enterprise edition if you want to scan Exchange, SQL Server, and file server data, or if you have many machines to manage and want centralized control of searches, results reporting and remediation.

Identity Finder Mac Edition doesn’t search everything, but it does do a good job rooting out the most sensitive identity data within the types of documents commonly found in most users’ Documents folders.

There are good business reasons for adopting a tool like Identity Finder. For example, many companies today have a zero tolerance policy for the storage of personally identifiable information. Any Social Security numbers, credit card numbers, federal tax ID numbers, bank account numbers or other sensitive data is to be removed as soon as an employee has finished with them.

That’s fine going forward, but how do you find what long-forgotten documents are hidden on employees’ computers — like mine? A stolen laptop containing an archive of hundreds of Social Security numbers or credit card numbers could cause a lot of public embarrassment and legal headaches.

If you have one or two home or business computers, you could consider periodically performing multiple searches for personal identity information using a desktop search tool like Google Desktop, but Identity Finder makes the process much easier, and its AnyFind feature, which casts a wider net, is more thorough. Identity Finder lets you schedule regular searches and can save the results for later review — and it’s fairly inexpensive.

I’d recommend going with the Professional edition. The free edition is simply too limited, and for $10 more than the Home edition, you’ll have the full-featured product.

Robert L. Mitchell is a national correspondent for Computerworld. Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/rmitch, or e-mail him at [email protected].